Don’t Defend a Mutiny

When I joined the Bush Administration, I went through the standard on-boarding process at the Department of Labor. At the end of the process, I raised my right hand and recited the following oath of office.

“I, Brian Schoeneman, do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.”

This was the same oath that I took when I joined the Navy ROTC when I turned 18. It was the same oath I would give four years later when I was sworn in as a licensed attorney in Virginia by then Virginia Supreme Court Chief Justice Cynthia Kinser. It was the same oath I gave two years later when I was sworn in as a member of Fairfax County’s Electoral Board.

That oath is pretty important to me, and in every job where I was required to take it, I worked hard to fulfill it to the best of my abilities. That oath bound me to support and defend our Constitution. What it did not do was give me the right to substitute my judgment for that of my superiors.

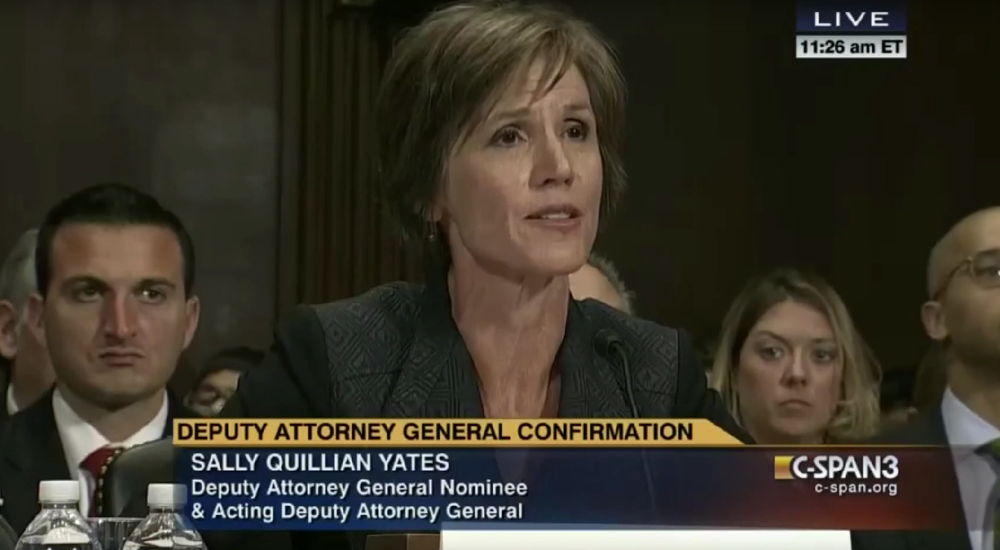

When Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, an Obama Administration appointee and national security holdover at the Department of Justice, decided that she didn’t want to defend President Trump’s Executive Order on refugees, she was not upholding her oath to the Constitution, or refusing to implement an illegal order. What she was doing was trying to substitute her professional opinion for that of the President. That’s not appropriate, nor was it her role.

Yet it’s a familiar thing that has been happening all too often across the United States lately, and it’s a trend that has to stop. We’ve seen it multiple times from our elected Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring, who has declined to represent laws he personally disagrees with multiple times, including on things like voting ID (since held constitutional by the courts) and the Marshall-Newman anti-gay marriage amendment (since held unconstitutional by the courts). Lawyers have been deciding that their personal stance on laws, or even their professional opinion on the constitutionality of a law overrides that of their superiors, so they decline to defend the law or, in Yates case, order all of their subordinates to decline to defend the law.

That’s not how the law works. That’s not how the oath we’ve all taken works. And it’s not how executive agencies work.

That is, to borrow a Navy term, mutiny. The UCMJ defines mutiny as acting “with intent to usurp or override lawful [] authority, refuse, in concert with any other person, to obey orders or otherwise do his duty …” That’s essentially what Sally Yates did. She acted with intent to override the President’s lawful authority and refused to do her duty.

It wasn’t a principled stand against a policy she disagreed with, and even if it were, it is inappropriate for any subordinate officer to try to override the lawful authority of their superiors simply because they disagree. That’s no way to run a government or any agency, especially not one that’s primary focus is law enforcement. DOJ is not an independent agency, and it’s not a creature of the Constitution. Sally Yates was never elected to anything, and while she was confirmed by the Senate, her power comes from Congress, who created her job and her agency, and her authority flows from the President, who is the chief magistrate and head of the executive branch, of which DOJ is a part.

It is not her job to decide whether a law or executive order is constitutional. She doesn’t have that authority. She can raise questions, she can make arguments, she can advise the President that in her opinion what he’s asking for is likely to be overturned by a court. She is not, however, a court. Her opinions are not binding. And she does not, under our system of government, have the power to override an executive action, or to substitute her judgment for the President’s simply because she disagrees with what he’s done.

That’s what she tried to do yesterday. Imagine the chaos if every single federal employee who has taken the oath to support and defend the Constitution suddenly chooses to arrogate the power to decide whether the actions they are ordered to take are constitutional or not. Imagine if every soldier on the battlefield gets to evaluate, based on his own opinion, whether the war he’s fighting is constitutionally valid. Imagine if every janitor at the Department of Education gets to decide whether the Department of Education itself is constitutional and deserves to have its halls swept. Imagine if every contractor at NSA gets to decide whether the data collection program they’re involved in violates the 4th amendment, and then chooses to hand the info over to a third party and escape to Moscow.

That’s not how our government has worked in the past, and it’s not how it’s supposed to work now. At its heart, for an attorney, this is question of professional ethics. As a DOJ lawyer, your client is the government of the United States.

As AAG Yates said in her hearing to this pointed question from Senator Jeff Sessions (ironically, President Trump’s Attorney General nominee), her role is to follow the law and the constitution, and provide her independent legal advice to the President. If the President chooses to ignore that advice, so be it – it is not her role, or the role of anybody else within the Executive Branch, to substitute their opinion on what is constitutional or proper for the President’s. He’s the one who was chosen by the American people to see the laws faithfully executed, not them. They are assisting him in doing that, but in the end, it is his responsibility. If what he is doing is unconstitutional, a court will make that determination after they have weighed the arguments for and against in an adversarial hearing with both sides represented.

This is what happened multiple times during the Obama Administration, where the same Justice Department that Sally Yates worked for went to court and argued that the actions taken by the President were constitutional – and courts disagreed, finding their actions unconstitutional. It happened in the Obamacare case, where DOJ argued that threatening states with cutting off their Medicaid funding in order to pressure them into creating health care exchanges was constitutional – the Supreme Court said it was not. It happened when President Obama tried to use recess appointments to fill the NLRB – DOJ argued it was constitutional, the Supreme Court said it was not. It happened on President Obama’s executive order on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program – DOJ argued it was constitutional, the Supreme Court deadlocked, leaving in place a lower court ruling that said it was not.

Would it have been appropriate in any of those cases for DOJ to decline to defend those laws because they felt they were unconstitutional? No, it would not have been. This is one of their primary responsibilities – to defend laws and actions taken by the government before the courts, whether they agree with them or not, or whether they believe the laws are constitutional or not. The decision as to constitutionality is not in the hands of any inferior officer of the Executive Branch. Period.

Lawyers have an ethical responsibility to represent their clients. If a client demands you do something you feel is improper or unethical, you have an obligation to counsel them not to go through with it. If they insist on engaging in the illegal behavior, or demand you do something improper, your only ethically responsible path forward is to withdraw from the representation – and if you’re an in-house attorney or you work for the government, that means resign. The ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct are pretty clear in this regard: “a lawyer shall not represent a client or, where representation has commenced, shall withdraw from the representation of a client if: (1) the representation will result in violation of the rules of professional conduct or other law[.]” If Yates truly felt this order violated the law, she was ethically required to withdraw from the representation. Even if she couldn’t say for sure that the President’s order violated the law (and she refused to say flat out it was a violation in her explanation of her action, instead saying “I am not convinced [it] is lawful“), the same model rules gave her an out by authorizing withdrawal when “the client insists upon taking action that the lawyer considers repugnant or with which the lawyer has a fundamental disagreement[.]”

That’s what happened during the Nixon Administration, when President Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire Independent Watergate Prosecutor Archibald Cox. Richardson refused, and resigned in protest. Nixon then turned to Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelhaus, who also refused and resigned. Solicitor General Robert Bork, who was sworn in as Acting Attorney General, followed Nixon’s order and fired Cox. A federal court later found that the firing of Cox was unlawful. Did that make what Bork did a violation of his oath of office? No. He was following what he felt was a lawful order at the time. It wasn’t his decision about whether the order was lawful or not. Richardson and Ruckelhaus did the responsible thing – resigning in the face of an order they felt honor bound to disobey after promising the Senate Judiciary Committee not to fire Cox without cause – but their action was not based on their oath of office.

Sally Yates should have resigned, rather than trying to trigger a constitutional crisis because of her disagreement with the President’s policy, which has not yet been invalidated by the courts, even if some of the implementation – arguably improperly handled by subordinates at CBP – has been put on hold by federal courts temporarily. Ultimately, a Court will decide if the President’s Executive Order is valid, not a lawyer at the Department of Justice.

President Trump’s quick action to implement his campaign promises using powers already delegated to the President by Congress has angered many Americans. We’ve seen protests in the streets almost daily since his inauguration. The refugee and travel executive order has been the most controversial, and in the face of such controversy, it’s critical that the law be evaluated in a cool, calm and collected manner. Sally Yates’ action was none of those. It was not a principled stand, speaking truth to power.

It was a mutiny.

The correct response for any lawyer in this situation was to resign. She chose to make a political statement and was fired, instead. And gasoline was poured on a fire in a way that does no one any credit.

Sally Yates tried to substitute her judgment for the President’s. She tried to override his lawful authority, and refused to do her duty. This is not laudable, it’s not professional, and it’s not behavior that should be encouraged.