According to state police, 1,939 law enforcement officers were assaulted in 2019 alone [1]. So why are Virginia Democrats trying to reduce penalties for assaults against our brave first responders? It’s madness!

As Senator Marco Rubio says, “it’s insane. [2]” As Senator Tom Cotton says, “It’s unhinged [3].” Tucker Carlson accuses Democrats of “targeting” police officers [4].

It’s Open Season on cops! And its a perfect case study for why criminal justice reform is so impossible to achieve.

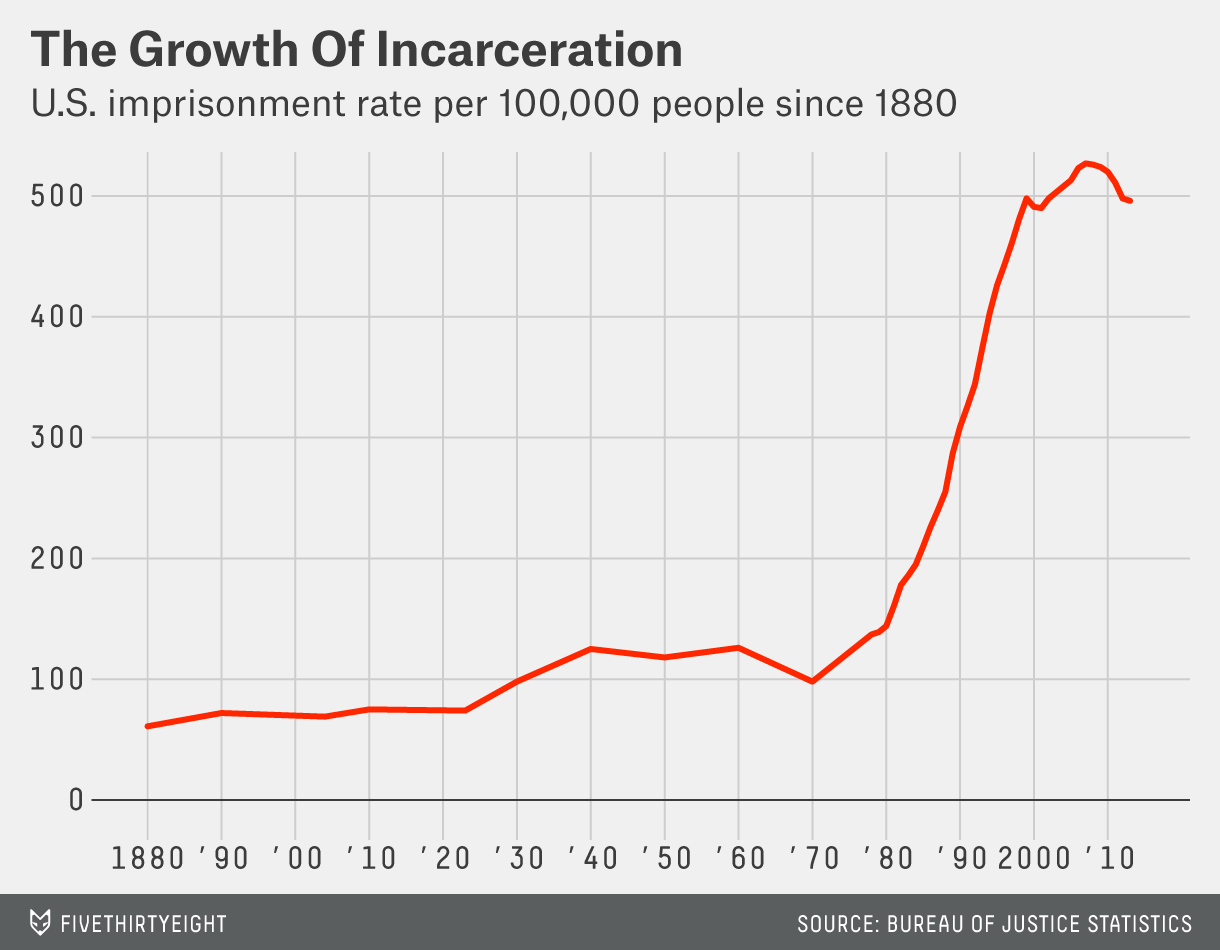

It’s a thousand times easier to be “tough on crime” than it is to evaluate flawed incentives in legislation and work to fix them. This is why violent crime is an at a 30-year low but in the “land of the free,” we lock up more people than any other country – by a lot [5].

One example of a new “tough on crime” law passed in 1997, when Virginia made “assault on a law enforcement officer” a felony, carrying a mandatory minimum of 6 months in prison. So what’s the issue? Why change it?

Most Assaults Don’t Involve Injury

First, assault is a broad term. Broader than you probably think. If you’ve ever heard or used the phrase “assault and battery,” you’ve made the distinction without even knowing it. Assault can mean as little as threatening to harm someone, or even making somebody believe that you intend to harm them. It can also include incidental or non-injurious contact.

How does this play out? If you get pulled over for a driving infraction, the cop reaches inside your car, and you move to push his hand out of the way – that’s assault.

If you’re being arrested and put into a squad car, trip, and grab onto a cop to catch yourself, that can be assault.

If you get upset in a hospital cafeteria and throw things around the room, and an onion ring hits a cop [7], that can be an assault.

This bill [8] clarifies the definition of felony assault to be one that “causes bodily harm.” Other cases, without harm, are still assault, but of the misdemeanor variety.

Go back to that figure from the state police. Of the 1,939 assaults, 1,327 of them – or 68% – resulted in no injury to the officer. Two out of 3 cases of “assault” are on the lower end of the scale, like incidental contact or an officer interpreting something as a threat. Those cases would still be punished! But as a misdemeanor rather than a felony.

And, obviously, assault on an officer or other first responder that results in bodily harm would remain a felony.

Some are concerned that harm needn’t be physical harm to be treated as significant. James Bacon gives examples [9] of a thrown bag of feces or laser pointers that can blind people. Of course, in these examples, a prosecutor can still make the determination to charge a felony if they feel it rises to the level of “bodily harm.” And even a misdemeanor charge can result in up to a year in prison. But Bacon also acknowledges that trivial offenses shouldn’t be felonies.

Why is it so important to make the distinction between a felony and a misdemeanor, especially if either can result in prison time? A charge is a charge; put it before the judge and they’ll determine justice based on the evidence, right? That’s what the police union says [4]: “We believe the courts are fair in how they apply the facts of the case to the law.”

Wrong.

Mandatory Minimums Ignore Facts of the Case

That’s the second reason this change is needed: because of mandatory minimums. Mandatory minimums say that, regardless of the individual facts of a case, a one-size-fits-all punishment applies, determined by lawmakers long before your crime occurred. Felony assault has a mandatory minimum of six months.

In the onion ring case above, a woman having a bad day and throwing a tantrum resulted in an onion ring hitting a cop. If convicted, that act alone would have left the judge with no choice but to sentence her to six months in jail. Even if the judge, based on the facts of the case, felt that the sentence far outweighed the crime, there is no possible way to apply a lighter sentence.

Apply that to all of the 1,327 cases of assault on a police office that resulted in no harm. All carry a minimum 6-month sentence. With a misdemeanor conviction, a judge could still determine the facts of a case and sentence them to six months, or even longer if deserved. But of course, most cases don’t go to trial; they get pled out.

The onion ring woman pled out. She was charged with two counts of assault (one for the onion ring, one for allegedly spitting at an officer) and one count of making a bomb threat. She hired a lawyer and these were all reduced to “disorderly conduct” and probation. Given the nature of the “crime” (a tantrum in a cafeteria), that seems more fitting. Justice was served!

But what about cases where the defendant can’t afford an attorney? What about cases assigned to hard-nosed prosecutors, or even those just having a bad day and not in a mood to reduce the charges? What about cases where the police ask or pressured the prosecutor to not be lenient?

Or, what about cases like a drug raid or a traffic stop with suspicion of drugs in the car where the evidence came back lacking or insubstantial, so the prosecutors assemble an array of charges without ever having the intent to argue the matter in front of a jury?

Over 90 percent of crimes don’t go to trial. That means the application of justice isn’t in the hands of a judge or jury; it up to the prosecutor to work out a deal. Every plea deal is a negotiation and the most valuable currency is leverage. The more crimes you can charge, the greater the leverage.

Especially when those crimes are felonies that have a mandatory minimum. Even if your “assault” didn’t actually result in any injury, you still have a six-month sentence hanging over your head to encourage you to plead “guilty” to a lesser offense. Why risk half a year in prison and spend thousands of dollars on a lawyer when you can just take probation, or a few days in prison, and a rap sheet?

It’s not like having a record is any sort of hindrance to your job prospects or ability to apply for benefits or maintain custody of your children, right?

Liberty is Hard; Lying Is Easier

Punishing assaults that result in no harm as misdemeanors rather than felonies is a no-brainer. It’s a needed correction to a bad bill passed 23 years ago. It should pass unanimously, especially with the support of those who love to talk about “freedom” and “liberty.” But it won’t, because its easier to be “tough on crime” and the enormous political incentives to lie about your partisan opponents.

And let me be clear: it is a lie. Republican legislators and commentators who claim this is “open season” on cops and first responders are lying to you.

Senators who claim this “endangers police” are lying to you. Tom Cotton is lying to you. Marco Rubio is lying to you.

Newspaper headlines who misrepresent what the legislation does for the sake of social media engagement are lying to you.

You’d think that Republicans who were so quick to crow about Joe Biden’s support of the 1994 Crime Bill and gleefully gloat about Kamala Harris’s record as a “cop” would be lining up to support such clear-cut opportunity to reverse injustice and demonstrate their criminal justice reform bona fides.

If they were interested in a good faith debate, they would be making their case against the bill on its merits. They would be talking about why it’s necessary for incidents with no harm to still be classified as felonies. They would be arguing why lawmakers can better determine a sentence than the judge of a case. They would explain to Virginians that while they love liberty, an onion ring hitting a cop should result in six months jail time.

But it’s easier to lie instead. And it is more advantageous to score political points than it is to correct the wrongs of overcriminalization. That’s why actual criminal justice reform is so impossible to achieve.