Perhaps you’ve heard about the oncoming “demographic disaster” for the Republican Party? This trope has been around for decades; here’s a book from 2002 called “The Emerging Democratic Majority”. That was followed by George W. Bush’s successful re-election in 2004.

Here’s a panel from 2009 featuring Ed Gillespie, future V.P. Mike Pence, Tim Pawlenty, and Mark Sanford about the future of the Republican Party in the face of troubling demographic trends. The following year, Republicans would take 60+ House seats in a Tea Party wave.

After President Obama’s re-election in 2012, Slate posted this ominous article about the GOP’s “demographic destiny”, saying if it couldn’t win in 2012, “it’s unlikely to ever [win] again.” Rinse, repeat, 2o14.

And, of course, articles from 2015 and 2016 that hammer at this same theme, before the Republican Party won control of the White House and both chambers of Congress in November 2016 (albeit, with President Trump losing the popular vote with only 46% of the vote). Even here at Bearing Drift, our own Matt Walton wrote about it.

So when David Brooks took to the NYTimes this week to talk about “The Coming GOP Apocalypse“, the established pattern from the previous 17 years indicates that we should be skeptical if not dismissive of warnings, right?

I’m not so sure. In fact, the major quibble I have with Brooks’s column is that it is written in the future tense, warning about an electoral wipeout to come, rather than the past tense. In reviewing the numbers, I think it’s now clear that we’ll look back at 2017 and 2018 “blue waves” as the canaries in the coal mine.

The 2018 mid-term elections, where Democrats picked up 40 seats in Congress in a Blue Wave (including three in Virginia), was most notable for its high turnout. Not only did turnout greatly exceed that of 2014’s (which actually had quite a low turnout), but it approached Presidential levels across the country and across Virginia.

Turnout was high in both parties, but higher among Democrats, and suggestive that the energy on Team Blue against the President helped mobilize voters among non-typical midterm voters, including minorities and young voters. Last week, the Census Bureau released 2018 voter data — and Pew was able to quantify and validate those suggestions.

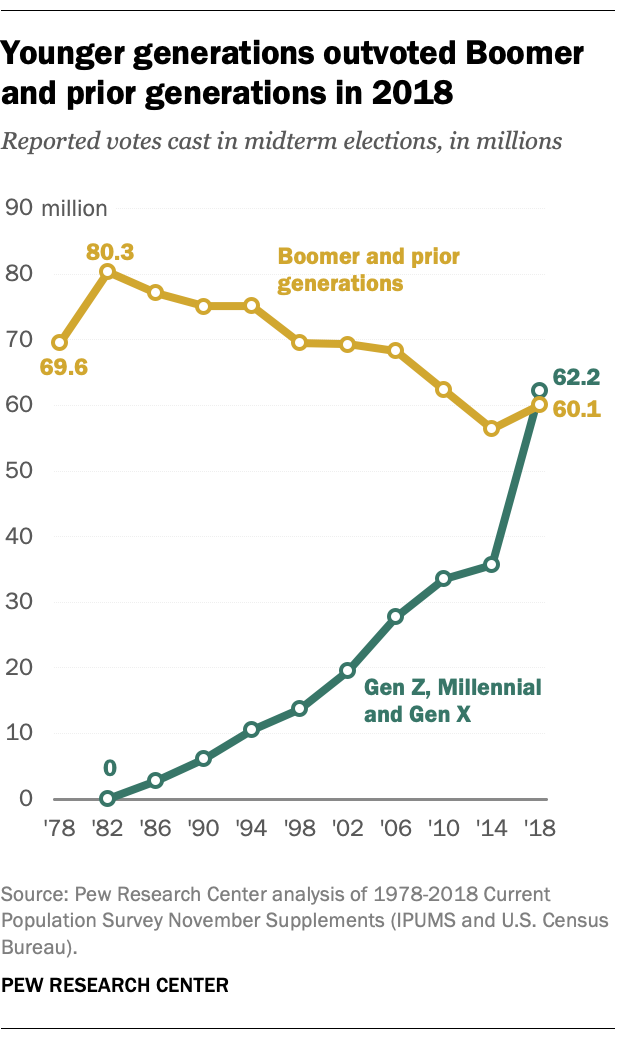

For the first time, Boomers and older generations (roughly age 55 and older) were out-voted by the combination of Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z:

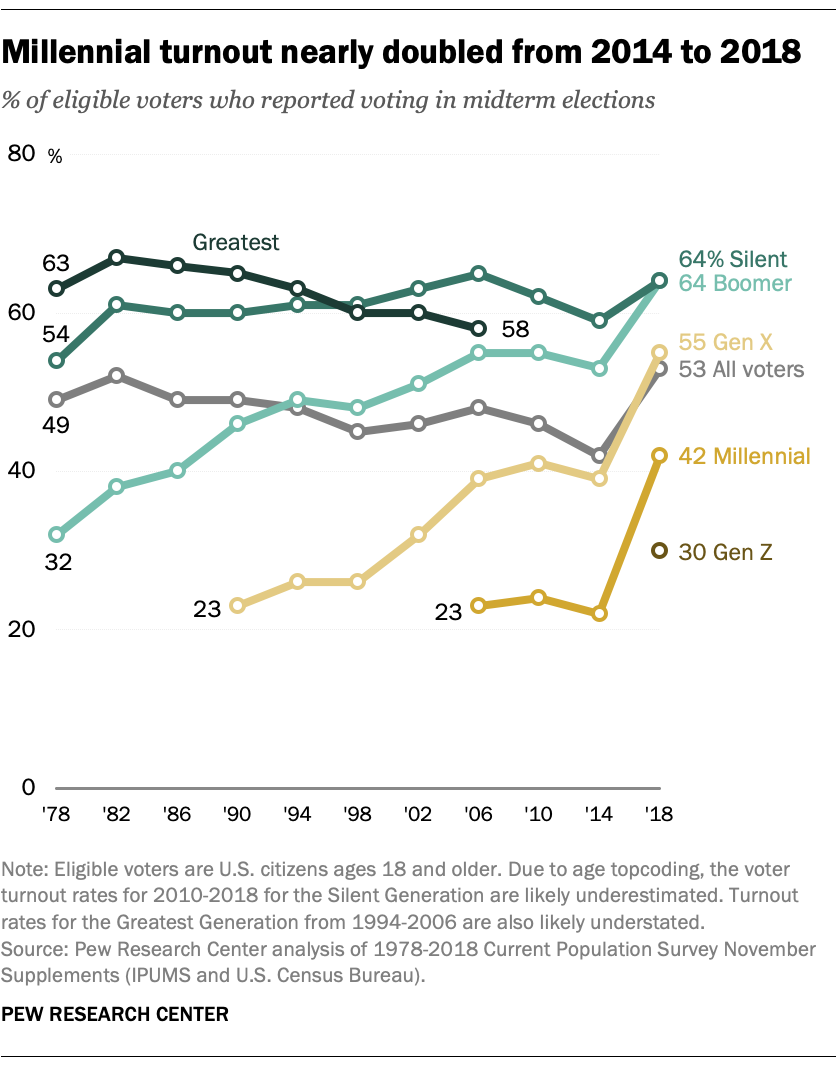

This trend will only increase as the post-Boomer generations become a larger part of the electorate. But it’s not just pure demographics, aging, and actuarial changes that are impacting the shape of the electorate. Turnout percentage (% votes cast out of eligible) also jumped dramatically from 2014 to 2018 among Millennials:

You can see that all generations jumped from 2014 (a low turnout midterm) to 2018 (a high turnout midterm); however, the jump for Boomers, from 53% to 64%, represents only a 21% increase from 2014. Meanwhile, the jump from 21% to 42% for Millennials is a 100% increase. And Gen Z, who weren’t eligible for vote in 2014, started their turnout percentage at 30%; where as Millennials started theirs back in 2006 at 23%.

You may be saying, so what? As people get older, or they get their first paycheck, they’ll get more conservative. However, Pew’s historical trends show a different story. Generation X is defined, roughly, as those born between 1965 and 1980; which means they started voting from 1983 to 1998. Pew only has self-identified party trends going back to 1992, so what’s most important here is the first third of the chart, showing the self-identified party ID for Gen X when they were young — and for some, voting for the first time:

Look at the same for Millennials (1981 to 1996, so their first vote in 1997 to 2014):

Here are the two takeaways from these charts:

1) It is only a recent phenomenon that younger voters are more liberal or Democrat; back when Generation X voters were young, party ID was roughly 50/50. It’s only this newest generation, Millennials, that have shown a distinct party advantage for Democrats. This suggests that whatever political calculus we relied on in previous decades may no longer apply.

2) Party ID is largely static. Both Gen X and Millennials (and Boomers before them, view the charts/data here) see only minor fluctuation in their party ID. This means if Millennials currently self-identify as Republicans in the mid-30s range and as Democrats in the mid-50s range, the pattern of previous generations suggests they will remain in those ranges as they continue to age and become larger parts of the electorate.

So Millennials are definitively more Democratic than Gen Xers, and are likely to stay that way. What about the newest Generation, Gen Z? Defined as born in 1997 or later, this generation became vote-eligible in 2015, meaning 2016 is their first election. How did that go?

Pew Research, as always, is indispensable for this information. As most of Gen Z is not yet vote-eligible, Pew shies away from asking questions about partisanship or vote preference, as these are subject to significant change for teenagers and tweeners. Instead, it looks at underlying social environments and attitudes. What did it show? I’ll let Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson field that one:

I am often asked if the pendulum will swing back and if Gen Z might actually be more right-leaning than the Obama-era Millennials. Current verdict: no. pic.twitter.com/q0V4q37uxC

— Kristen Soltis Anderson (@KSoltisAnderson) January 17, 2019

Where does that leave us? By 2020, 37% of the electorate is projected to be Millennials or Gen X. The trendlines can tell you where those numbers will continue to go:

The natural question is “what can be done?” But political parties rarely rally behind a strategic course correction, and are largely shaped by the policy preferences and character of its prominent leaders. That’s why, from 2016 to present, both political parties are in favor of raising taxes and increasing the size of government; the primary difference is which groups of people they wish to use the power of the state to benefit.

For today’s Republican Party, that means embracing a hostility towards immigration that is simply unacceptable to younger generations. There are still some sweet summer children in the Republican Party who proudly stand up and say silly things like, “Republicans aren’t opposed to immigration, just illegal immigration”

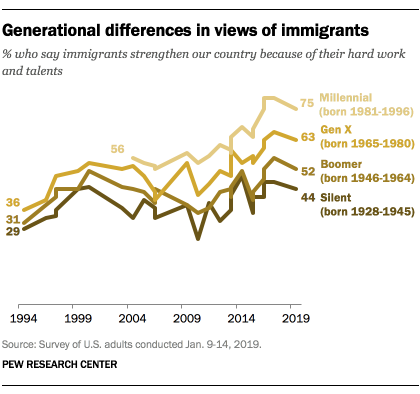

Consider the central question of whether legal immigration strengthens or burdens the country:

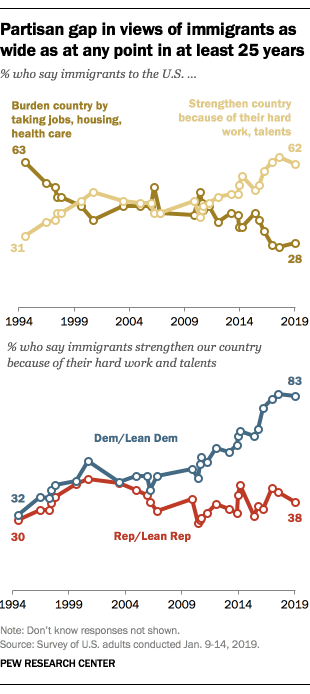

Quite obviously and overwhelmingly, younger voters differ from older voters. But even more so, they differ from Republicans:

That is, 75% of Millennials, but only 38% of Republicans, say legal immigrants strengthen the country.

Republicans are marching down this path, convinced that’s where the base wants them to go. They’re largely being driven there by anti-immigrant voices like Tucker Carlson, who said that immigration makes the U.S. “poor and dirtier and more divided”, and Laura Ingraham, who claimed that the country is changing in ways Americans don’t like thanks to legal immigration. Michelle Malkin earned a standing ovation at 2018 CPAC in a speech largely remembered for attacking the “ghost of John McCain”, but what went less noticed is Malkin’s entire rant was decrying the impact of legal immigration, concluding with the remark that “Diversity is NOT our strength” (transcript here).

On that topic of diversity, Pew shows that the newest generations disagree with the CPAC crowd, as 61% of Millennials and 62% of Gen Zers say that diversity is good for society. That’s, perhaps, due to the fact that Generation Z is on track to be the most diverse generation on record, with 48% who are “non-white” (a term that will become increasingly en vogue as the term “minority” becomes unfactual).

This is notable not just because the denizens of Generation Z are themselves diverse, but even the slim white majority of Generation Z are growing up alongside with and within this diverse ecosystem. Anti-immigrant sentiment is generally concentrated in the least diverse geographic regions of the country; the same holds true for generations.

Reversing course on these trends likely won’t happen until 2021 at the earliest. At that point, the Republican Party will need to ask themselves if they want to be the party of Stephen Miller and Michelle Malkin, or if they want to be the party of Abraham Lincoln and Ronald Reagan. Even still, it may be too late to reverse these generational partisan trends. At this point in time, the Republican Party isn’t at risk of losing the youth vote; as 2018 has shown, it has already lost it.

Banner image credit: Jeff Miller / University of Wisconsin-Madison